Robert Frost

THE BEAR

And draws it down as if it were a lover

And its choke cherries lips to kiss good-bye,

Then lets it snap back upright in the sky.

Her next step rocks a boulder on the wall

(She's making her cross-country in the fall).

Her great weight creaks the barbed-wire in its staples

As she flings over and off down through the maples,

Leaving on one wire moth a lock of hair.

Such is the uncaged progress of the bear.

The world has room to make a bear feel free;

The universe seems cramped to you and me.

Man acts more like the poor bear in a cage

That all day fights a nervous inward rage~

His mood rejecting all his mind suggests.

He paces back and forth and never rests

The me-nail click and shuffle of his feet,

The telescope at one end of his beat~

And at the other end the microscope,

Two instruments of nearly equal hope,

And in conjunction giving quite a spread.

Or if he rests from scientific tread,

'Tis only to sit back and sway his head

Through ninety odd degrees of arc, it seems,

Between two metaphysical extremes.

He sits back on his fundamental butt

With lifted snout and eyes (if any) shut,

(lie almost looks religious but he's not),

And back and forth he sways from cheek to cheek,

At one extreme agreeing with one Greek~

At the other agreeing with another Greek

Which may be thought, but only so to speak.

A baggy figure, equally pathetic

When sedentary and when peripatetic

Robert Frost

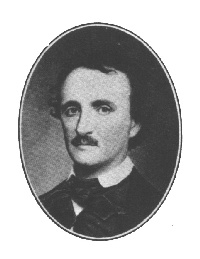

biography of Edgar A.P

Poe, a great 19th-century American author, was born on Jan 19, 1809, in Boston, Mass. Both his parents died when Poe was two years old, and he was taken into the home of John Allan, a wealthy tobacco exporter of Richmond, Va. Although Poe was never legally adopted, he used his foster father's name as his middle name.

After several years in a Richmod academy, Poe was sent to the

University of Virginia.

After a year, John Allan refused to give him more money,

possibly because of Poe's losses at gambling. Poe then had to leave

the university.

In 1827 he published, in Boston, Tamerlane and Other Poems. This

was the first volume of his poems, and was published anonymously. The

book made no money, and Poe enlisted in the United States Army under

an assumed name. After he served two years, his foster father arranged

for him to be honorably discharged and to enter the United States

Military Academy. But, within six months, Poe was dismissed because of

neglect of duty.

Poe then began to write stories for magazines. In 1831, he published

Poems by Edgar A. Poe, which he dedicated to the cadets of the

U.S. Military Academy. In 1833, he won a cash prize for the story

MS. Found in a Bottle.

In 1835, he jointed the staff of the

Richmond Magazine, Southern Literary Messenger. Within a year,

the circulation of the magazine increased seven times thanks to the

popularity of Poe's stories.

Poe, however, soon lost his job with the magazine because of his

drinking. In 1836, he married beautiful Virginia Clemm, the

13-year-old daughter of his aunt. The following year he lived in

New York City, and the next year he drifted to Philadelphia. There

he became associate editor of Burton's Gentleman's Magazine.

He contributed literary criticism, reviews, poems, and some of his

most famous stories to this magazine.

In 1840, Poe published Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque,

a two-volume set of his stories. As literary editor of Graham's

Magazine, he wrote the famous stories, A Descent into the Maelstrom,

and The Masque of Red Death. In 1843, Poe won a prize of his story

The Gold Bug. This story, along with such earlier tales as The

Purloined Letter and The Murders in the Rue Morgue, set the standard

of the modern detective story. He reached the heights of his fame in

1845 with his poem The Raven.

That same year he was appointed literary critic of the New York Mirror.

The long illness of Virginia Poe and her death in 1847 almost wrecked

Poe. His mental and physical condition grew steadily worse, and he tried

to commit suicide. Still, in 1848 and 1849 Poe was able to deliver a

series of lecture tours. He died in 1849 in Baltimore, and the notes

from his lectures were published posthumously in 1850, under the title

The Poetic Principles. The work, along with The Rationale of

Verse (1843) and The Philosophy of Composition (1846) ranks

among the best examples of Poe's literary criticism.

Edgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe

Alone

From childhood's hour I have not been

As others were; I have not seen

As others saw; I could not bring

My passions from a common spring.

From the same source I have not taken

My sorrow; I could not awaken

My heart to joy at the same tone;

And all I loved, I loved alone.

Then- in my childhood, in the dawn

Of a most stormy life- was drawn

From every depth of good and ill

The mystery which binds me still:

From the torrent, or the fountain,

From the red cliff of the mountain,

From the sun that round me rolled

In its autumn tint of gold,

From the lightning in the sky

As it passed me flying by,

From the thunder and the storm,

And the cloud that took the form

(When the rest of Heaven was blue)

Of a demon in my view.

Robert Frost poem

A Christmas circular letter

And left at last the country to the country;

When between whirls of snow not come to lie

And whirls of foliage not yet laid, there drove

A stranger to our yard, who looked the city,

Yet did in country fashion in that there

He sat and waited till he drew us out

A-buttoning coats, to ask him who he was.

He proved to be the city come again

To look for something it had left behind

And could not do without and keep its Christmas.

He asked if I would sell my Christmas trees;

My woods -- the young fir balsams like a place

Where houses all are churches and have spires.

I hadn't thought of them as Christmas Trees.

I doubt if I was tempted for a moment

To sell them off their feet to go in cars

And leave the slope behind the house all bare,

Where the sun shines now no warmer than the moon.

I'd hate to have them know it if I was.

Yet more I'd hate to hold my trees, except

As others hold theirs or refuse for them,

Beyond the time of profitable growth

The trial by market everything must come to.

I dallied so much with the thought of selling.

Then whether from mistaken courtesy

And fear of seeming short of speech, or whether

From hope of hearing good of what was mine,

I said, "There aren't enough to be worth while."

"I could soon tell how many they would cut,

You let me look them over."

"You could look.

But don't expect I'm going to let you have them."

Pasture they spring in, some in clumps too close

That lop each other of boughs, but not a few

Quite solitary and having equal boughs

All round and round. The latter he nodded "Yes" to,

Or paused to say beneath some lovelier one,

With a buyer's moderation, That would do.

I thought so too, but wasn't there to say so.

We climbed the pasture on the south, crossed over,

And came down on the north.

He said, "A thousand."

"A thousand Christmas trees! -- at what apiece?"

He felt some need of softening that to me:

"A thousand trees would come to thirty dollars."

Then I was certain I had never meant

To let him have them. Never show surprise!

But thirty dollars seemed so small beside

The extent of pasture I should strip, three cents

(For that was all they figured out apiece)__

Three cents so small beside the dollar friends

I should be writing to within the hour

Would pay in cities for good trees like those,

Regular vestry-trees whole Sunday Schools

Could hang enough on to pick off enough.

A thousand Christmas trees I didn't know I had!

Worth three cents more to give away than sell,

As may be shown by a simple calculation.

Too bad I couldn't lay one in a letter.

I can't help wishing I could send you one,

In wishing you herewith a Merry Christmas

Robert Frost

Mountain Interval

1916